DeTour Reef Lightkeeper Doesn’t Lead Lonely Life

By John T. Nevill

The Evening News, Sault Ste. Marie, Mich, December 10, 1951

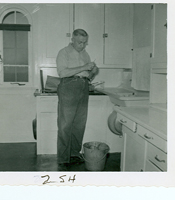

Keeper in Charge from 1940-1962, Charles Jones in the kitchen of DeTour Reef Light(1957)

DETOUR, Mich. – Charles R. Jones, head keeper on DeTour Reef Lighthouse stopped stirring a huge pot of stew long enough to answer our query.

Lonesome? Not particularly. As you can see a man has to do quite a few chores out here and that keeps him busy. Of course we naturally miss our families and friends, but we’re lucky out here. We manage to get ashore once or twice a week.

Just a few minutes before Mr. Jones having spotted our small Coast Guard boat coming out from the village waterfront, had managed the powerful crane which hooked our boat and raised it twenty feet above the bouncing water to the main level of the sixty by sixty crib. Now one floor above, in the lighthouse living quarters, he was preparing a tasty lunch for his three assistants, two Coast Guard radio technicians from the Sault and me.

29 Years

Charles Jones, a veteran of twenty-nine years in the U. S. Light- house Service – long before it was taken over by the Coast Guard – is proud of DeTour Reef Light because of its importance to Great Lakes shipping. Moreover, it is one of the most modernly equipped navigational aids to be found on the Great Lakes. Some of its equipment is so new and experimental we were requested to refrain from describing it at all.

DeTour Reef Light rests atop solid rock about twenty-seven feet below the surface at the end of a shallow boulder strewn reef extending menacingly from Detour Point on the mainland. Above the surface the light- house towers to more than seventy feet the huge 1600,000 candlepower light being more than sixty-nine feet above the normal water level.

When originally installed back in 1872[sic], DeTour Light was located at the end of the point on the mainland and was called DeTour Point Light. In 1931, however, the present crib-based light was erected at the end of the reef shoal three quarters of a mile off shore and is known as Detour Reef Light.. The wisdom of moving the light to the reef’s end is written in the record of boats which got into trouble trying to cross the reef.

Dangerous Spot

About three-quarters of a mile southeast of the present light, the ship lanes from every area of the Great Lakes converge. Those entering or leaving the St. Mary’s River are moving almost due north or due South, and therein lies the importance of DeTour Reef Light. Safe enough in clear weather. It is reported as one of the most dangerous spots on the Lakes in thick fog or snow.

DeTour’s main light which revolves and flashes for one-second every ten seconds originates in one 500-watt bulb. Just behind it – between the light and the mainland – there is a red sector which spells danger to any shipmaster able to see it. The rule, says Mr. Jones is this: If they can see the red flash, they’re too close to shore.

Besides the flashing light, the stations’ equipment includes a radio beacon sending four dashes through the ether for a distance of 100 miles in all directions, and an air operated diaphone or fog horn which can be heard for many miles. Frequency of the beacon depends upon the weather, thick weather calling for constant operation.

Jones joined the lighthouse service in 1922, his first assignment being at Thunder Bay Island. He remained at Thunder Bay until the spring of 1926 when he was transferred to the Portage Ship Canal ten miles northwest of Houghton. Ten years later he was moved to Big Bay Point thirty miles northwest of Marquette. Four years later in 1940 he was transferred to DeTour when the Big Bay station was discontinued.

At DeTour Reef Light, Jones is assisted by John J. Short, David S. Barkley, and Richard C. Parks each of the four being on duty for three weeks and off for one.

Duplicators

Every piece of equipment on the crib – including the radio beacon, but excluding the light itself and the experimental equipment – is duplicated. Thereby assuring constant operation.

Broke Every Window

A man with 29 years in the light house service is certain to have a storm or two to remember and Charley Jones is no exception. The storm he remembers best is the big blow of November 11, 12, and 13, 1940.

Known as the Armistice Day storm, this disturbance swallowed up a lot of boats, including the freighters William C. Davock and Anna C. Minch along with their entire crews of thirty-three, and twenty-four respectively. It was centered in Lake Michigan but DeTour Reef Light got a healthy taste of it.

“The suddenness of the storm caught us unprepared,” said Mr. Jones. “The heavy steel shutters which usually are closed to protect our thick plate glass windows were open and once the storm burst, we didn’t dare send men out to close them.

“The windows are more than twenty feet above normal water level, but the waves, like somersaulting mountains rose up and crashed against them, breaking every window in the place. The two inch steel posts supporting the chain rail around the crib platform were bent over as though they were made of putty.

“That storm began with a wind coming out of the south. Later the wind switched to southwest, and for a time averaged eighty miles an hour. When, after three days, it subsided, we counted the damage.

“In addition to the broken windows and the bent over posts, we lost one row boat, and very nearly lost our power boat. But the crew gained something. They gained a great respect for Great Lakes storms.”

Note:

According to Chuck Feltner Historian for the DRLPS most of this article appears in a book that the reporter John T. Nevill wrote in 1956 entitled “Wanderings – Sketches of Northern Michigan Yesterday and Today”. Feltner cautions that there are some errors in article, but it is reprinted as it originally appeared in the Soo Evening News on December 10, 1951.